The Future will take us in Circles.

‘The circle has tremendous visual power. This is true of any circle, any size, in just about any composition. The human eye loves the circle and embraces it’.

—

Kimberly Elam

—

Kimberly Elam

Re – Quote #5 — LIFECYCLES

Re – Quote #5 — LIFECYCLES

As we walk through time, our unit of measurement when viewed on a clock is most easily understood in its circular motion. The second hand makes circles within the minutes, whilst the minute hand makes circles around the hours. As days pass to weeks, and months pass to seasons, these processes continue in their perpetual circularity. As soon as one summer finishes, we are already that much closer to the next. And as we live our lives we keep returning to the same physical and mental points over and over again, sometimes by necessity and sometimes by accident. We revisit these same reference points for reassurance, or as a means by which to help us learn.

Yet despite all this evidence that many natural processes are unavoidably circular, life on board this spinning rock at ground level can appear disappointingly much flatter. The passage of each day has a tendency to still feel repeatedly linear, as do many of our working processes. In our professional lives we habitually judge our activity through the completion of tasks, sometimes to the neglect of the overall experience, what we learnt along the way, or what our findings help us prepare to do next.

It was Pythagorus who first suggested the world was round sometime around 500BC, and Aristotle who first declared that the Earth was a sphere sometime close to 350BC. However people held onto their two dimensional perceptions for much longer, some believing the ocean to be filled with monsters large enough to devour whole ships. During the early Middle Ages, many Europeans succumbed again to these rumours, and started believing that they lived on a flat earth.

The myth of a flat earth was perpetuated by Christian Europeans long into the Middle Ages. They later used a similar manipulation of the facts to perpetuate a lie that an Italian named Christopher Columbus discovered America, despite the somewhat obvious fact there were already people living there. Blinkered falsities such as these can be linked throughout the Imperialist era to the very beginnings of 20th century Capitalism, and damaging belief structures such as ‘capitalist entitlement’.

Ignoring valuable lessons from either the 1st or 2nd Agricultural Revolutions where farmers first learnt the idea of the ‘rotation system’ and the importance of allowing time for the land to recover. Capitalism has long since perpetuated flawed ideas of linear economic and manufacturing systems. So much so, that much of our present day thinking can be unimaginatively flat in many aspects of our daily living. Some causes of unhappiness relate to this style of thinking, where on the sequential path, we have not reached the pinnacles of where we once expected we would be.

Maldonado tried to break this spell at the Ulm School of Design back in the 1960’s. Here he orientated the curriculum towards a balanced relationship between science and design, and between theory and practice, fully incorporating planning methods, perceptual theory and semiotics into the process. He was effectively aiming for more harmonious relationships between not necessarily complimentary elements. The optimum, he believed, embraced a fuller interpretation of both analytical and holistic thinking.

At the beginning of the 1959/60 academic year, Maldonado explained to his students: “Nowadays … design problems must be approached and solved on the basis of precise factual knowledge. We must admit that this knowledge is not easy to attain and that it demands a great deal from the students … For this reason, the academic year that begins today will be marked by an emphasis on methodology …”.1 Designers working this century to more mindful principles of making, might have great empathy for the consonance of this important feedback loop.

The notion of ‘Circularity’ which has re-emerged more recently, certainly is not new. But it is happily beginning to gain the attention which it has long deserved, particularly within the context of industrial processes and manufacturing. From new catchphrases such as the ‘Circular Economy’ to ‘Donut Economics’. We are finally getting much better at thinking and making in circles.

The idea of the circular economy catapults us to a more adaptable system which takes responsibility for the whole supply chain. It links the beginning of the process to the end so that whatever it is that you’re making, you care about where the raw materials and components have come from (at best they are carefully sourced from proven sustainable sources). You put the thing you’re making together in such a way that during its lifetime it is as clean, nonpolluting and energy efficient as possible. And most importantly, at the end of a life cycle, it can be disassembled, and the pieces re-used, re-cycled, or re-used for energy. This thinking replaces the old linear model with a more sustainable and circular method of making.

Now that new technology is allowing us to create previously unexplored connections not just in how we make, but also between the things we make, it will soon no longer be viable for any of our processes to continue to be flat, or treated in isolation. Old fashioned models which still sees us bury much of our waste in the ground, will one day seem as archaic as the belief that the world was once flat. The transformation may well hold a similar significance in world history as well.

According to Kate Raworth, the future is shaped like a donut. Rather poignantly she believes: “Humanity’s 21st Century challenge is to meet the needs of all within the means of the planet”.2 In other words, in order to ensure that no one falls short on life’s essentials – from food and housing to healthcare. We must also collectively ensure that we don’t overshoot our pressure on Earth’s life-supporting systems – a stable climate, fertile soils, and a protective ozone layer being amongst the essentials which we have taken for granted for far too long.

By thinking of the health of our ‘economics’ in terms of both the earth’s natural systems and those of human made society, Kate reminds us that we are more than just workers and consumers. We’re just as dependent on our natural systems, as well as the flow of energy and materials between the two. The Doughnut model, which illustrates the delicate balance between social and planetary boundaries, provides an alternative way to frame the challenge of creating harmony between the two, and acts as a valuable compass for our thinking throughout this next century.

With more circular systems in place, we might begin to see the process of manufacturing as closer to that of farming. Where a 'crop of products' is made (or cultivated) cyclically, consistently adjusting to changes in demand with each new cycle. ‘Garment farming’ already sounds like a more natural process than manufacturing. And suggests a system which could be more creative, flexible and organic too. Here ideas associated with the incoming Fourth Industrial Revolution may well prove to have more in common with previous practices from quite some time ago, and take greater inspiration from earth's natural systems as well.

360 degree processes can be applied to almost any system. From ‘Sponge Cities’ which are designed to capture and release rainwater in patterns similar to forests within the natural world. To ‘energy positive’ buildings which generate more energy than they consume. In circular models awkward problems get flipped to become tomorrow's solutions. Herbert Giradet nails it when he says “Continuous regeneration must be a guiding principle for human action”. He goes on to suggest ‘it is high time that these realisations were embedded in the teaching of economic theory at universities and business schools all over the world’.3 In the long-term it would be wise for these these ideas to be embedded into international law as well.

It’s here eventually we will get something that is no longer a set of connected systems, but an ecosystem instead. Brian Eno is fond of ecosystems because they’re closer to how human culture and the earth’s natural systems already behave. “Now this thing about ecosystems”, as he explains, “is that it’s impossible to tell what the important parts are. It’s not a hierarchy, you know. We’re used to thinking of things that are arranged in levels like that, with the important things at the top and the less important things at the bottom. Ecosystems aren’t like that. They’re richly interconnected and they’re co-dependent in many, many ways”.4

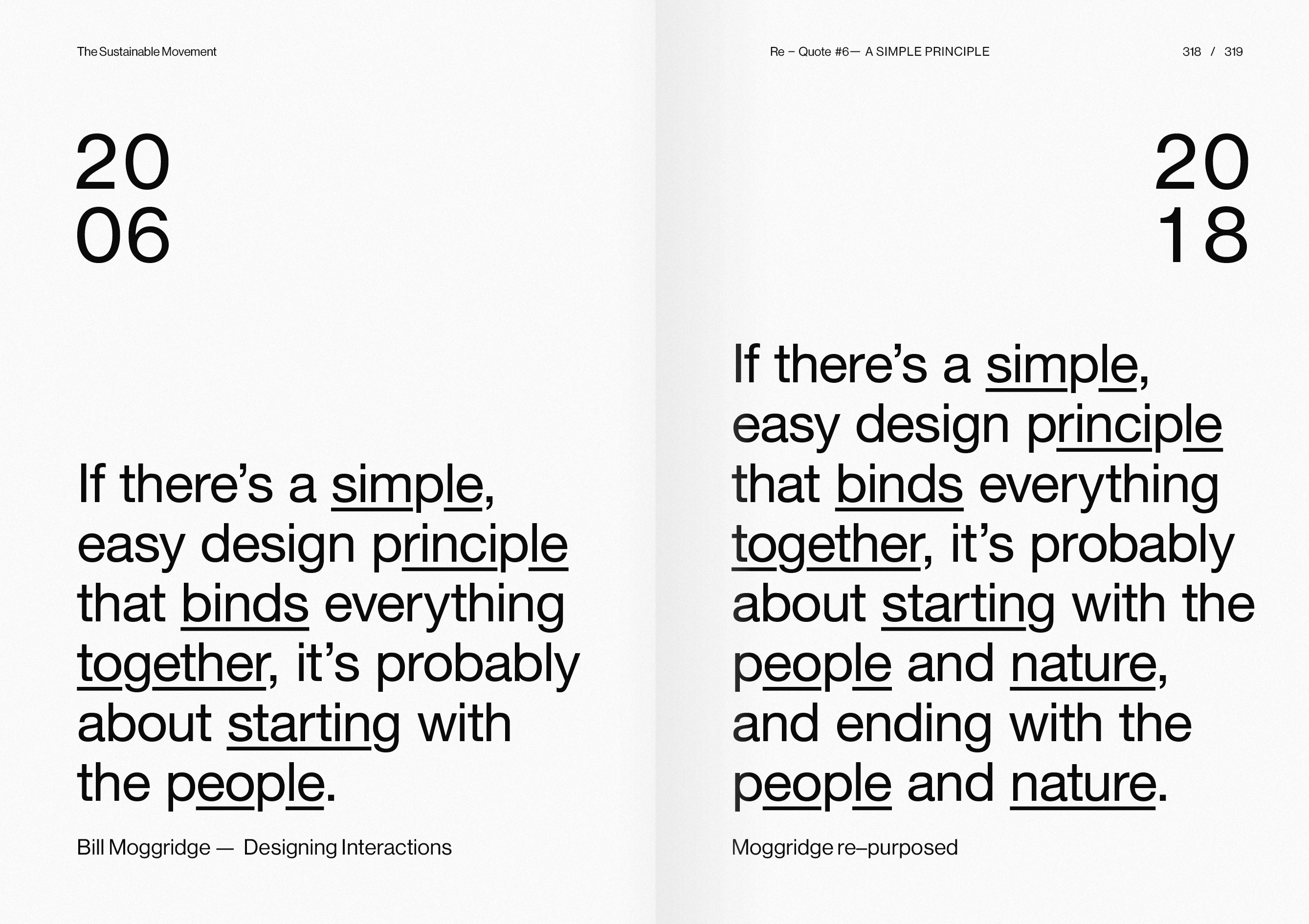

On the grand scale humanity has always attempted to create a better future through the continued process of imagining, re-imagining, dreaming, re-dreaming, working and re-working together. Always with the best knowledge we have at our disposal at any point in time. To adapt and ‘re-purpose’ an old Bill Moggridge quote: ‘If there’s a simple, easy design principle that binds everything together, it’s probably about starting with the people and nature, and ending with the people and nature’. To put this in its simplest terms, we’re essentially talking about creating more robust loops for living, aligned closer to earth’s cyclical processes, and then maintaining their harmony.

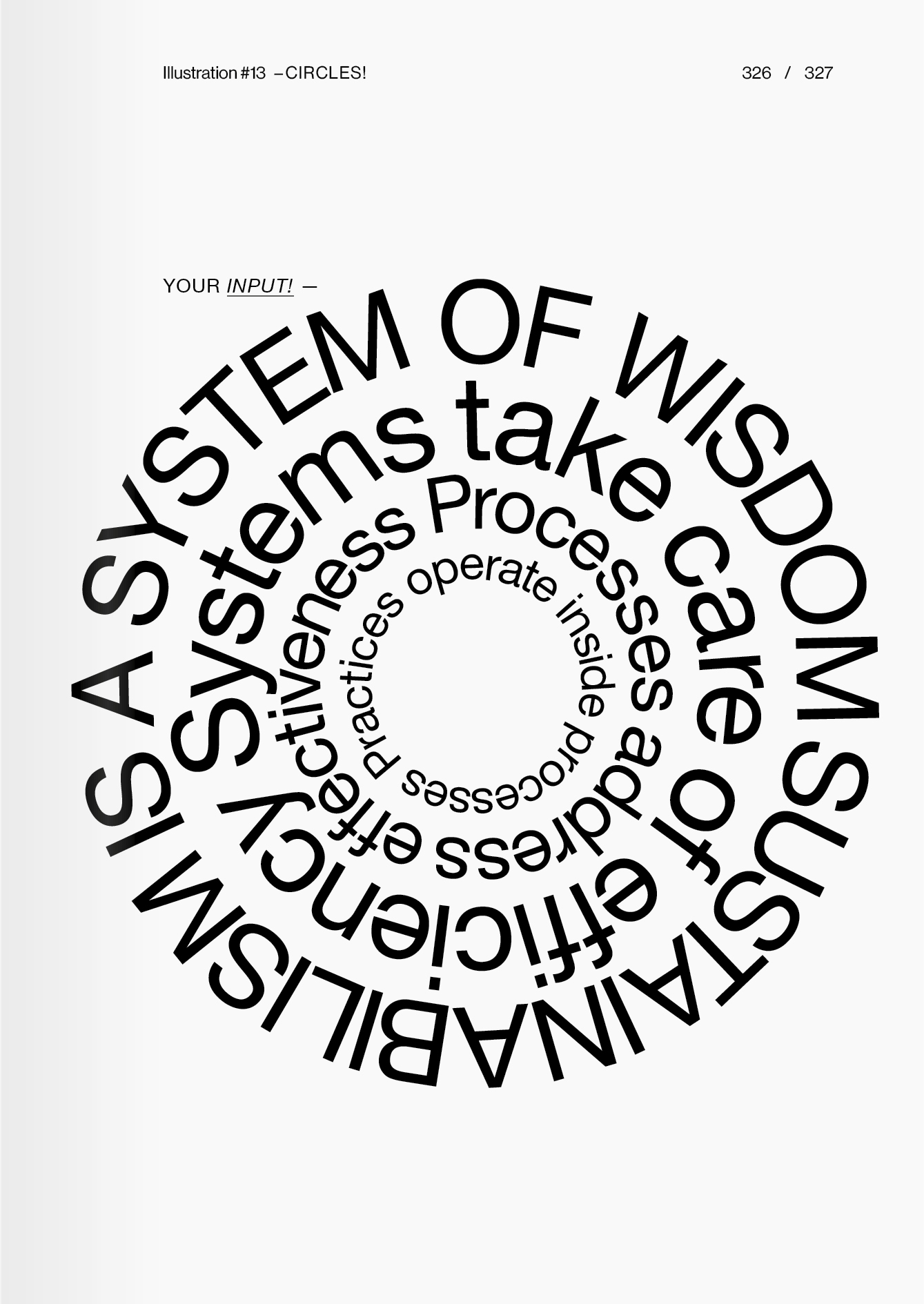

![]() Illustration – Circles!

Illustration – Circles!

Yet despite all this evidence that many natural processes are unavoidably circular, life on board this spinning rock at ground level can appear disappointingly much flatter. The passage of each day has a tendency to still feel repeatedly linear, as do many of our working processes. In our professional lives we habitually judge our activity through the completion of tasks, sometimes to the neglect of the overall experience, what we learnt along the way, or what our findings help us prepare to do next.

It was Pythagorus who first suggested the world was round sometime around 500BC, and Aristotle who first declared that the Earth was a sphere sometime close to 350BC. However people held onto their two dimensional perceptions for much longer, some believing the ocean to be filled with monsters large enough to devour whole ships. During the early Middle Ages, many Europeans succumbed again to these rumours, and started believing that they lived on a flat earth.

The myth of a flat earth was perpetuated by Christian Europeans long into the Middle Ages. They later used a similar manipulation of the facts to perpetuate a lie that an Italian named Christopher Columbus discovered America, despite the somewhat obvious fact there were already people living there. Blinkered falsities such as these can be linked throughout the Imperialist era to the very beginnings of 20th century Capitalism, and damaging belief structures such as ‘capitalist entitlement’.

Ignoring valuable lessons from either the 1st or 2nd Agricultural Revolutions where farmers first learnt the idea of the ‘rotation system’ and the importance of allowing time for the land to recover. Capitalism has long since perpetuated flawed ideas of linear economic and manufacturing systems. So much so, that much of our present day thinking can be unimaginatively flat in many aspects of our daily living. Some causes of unhappiness relate to this style of thinking, where on the sequential path, we have not reached the pinnacles of where we once expected we would be.

Maldonado tried to break this spell at the Ulm School of Design back in the 1960’s. Here he orientated the curriculum towards a balanced relationship between science and design, and between theory and practice, fully incorporating planning methods, perceptual theory and semiotics into the process. He was effectively aiming for more harmonious relationships between not necessarily complimentary elements. The optimum, he believed, embraced a fuller interpretation of both analytical and holistic thinking.

At the beginning of the 1959/60 academic year, Maldonado explained to his students: “Nowadays … design problems must be approached and solved on the basis of precise factual knowledge. We must admit that this knowledge is not easy to attain and that it demands a great deal from the students … For this reason, the academic year that begins today will be marked by an emphasis on methodology …”.1 Designers working this century to more mindful principles of making, might have great empathy for the consonance of this important feedback loop.

The notion of ‘Circularity’ which has re-emerged more recently, certainly is not new. But it is happily beginning to gain the attention which it has long deserved, particularly within the context of industrial processes and manufacturing. From new catchphrases such as the ‘Circular Economy’ to ‘Donut Economics’. We are finally getting much better at thinking and making in circles.

The idea of the circular economy catapults us to a more adaptable system which takes responsibility for the whole supply chain. It links the beginning of the process to the end so that whatever it is that you’re making, you care about where the raw materials and components have come from (at best they are carefully sourced from proven sustainable sources). You put the thing you’re making together in such a way that during its lifetime it is as clean, nonpolluting and energy efficient as possible. And most importantly, at the end of a life cycle, it can be disassembled, and the pieces re-used, re-cycled, or re-used for energy. This thinking replaces the old linear model with a more sustainable and circular method of making.

Now that new technology is allowing us to create previously unexplored connections not just in how we make, but also between the things we make, it will soon no longer be viable for any of our processes to continue to be flat, or treated in isolation. Old fashioned models which still sees us bury much of our waste in the ground, will one day seem as archaic as the belief that the world was once flat. The transformation may well hold a similar significance in world history as well.

According to Kate Raworth, the future is shaped like a donut. Rather poignantly she believes: “Humanity’s 21st Century challenge is to meet the needs of all within the means of the planet”.2 In other words, in order to ensure that no one falls short on life’s essentials – from food and housing to healthcare. We must also collectively ensure that we don’t overshoot our pressure on Earth’s life-supporting systems – a stable climate, fertile soils, and a protective ozone layer being amongst the essentials which we have taken for granted for far too long.

By thinking of the health of our ‘economics’ in terms of both the earth’s natural systems and those of human made society, Kate reminds us that we are more than just workers and consumers. We’re just as dependent on our natural systems, as well as the flow of energy and materials between the two. The Doughnut model, which illustrates the delicate balance between social and planetary boundaries, provides an alternative way to frame the challenge of creating harmony between the two, and acts as a valuable compass for our thinking throughout this next century.

With more circular systems in place, we might begin to see the process of manufacturing as closer to that of farming. Where a 'crop of products' is made (or cultivated) cyclically, consistently adjusting to changes in demand with each new cycle. ‘Garment farming’ already sounds like a more natural process than manufacturing. And suggests a system which could be more creative, flexible and organic too. Here ideas associated with the incoming Fourth Industrial Revolution may well prove to have more in common with previous practices from quite some time ago, and take greater inspiration from earth's natural systems as well.

360 degree processes can be applied to almost any system. From ‘Sponge Cities’ which are designed to capture and release rainwater in patterns similar to forests within the natural world. To ‘energy positive’ buildings which generate more energy than they consume. In circular models awkward problems get flipped to become tomorrow's solutions. Herbert Giradet nails it when he says “Continuous regeneration must be a guiding principle for human action”. He goes on to suggest ‘it is high time that these realisations were embedded in the teaching of economic theory at universities and business schools all over the world’.3 In the long-term it would be wise for these these ideas to be embedded into international law as well.

It’s here eventually we will get something that is no longer a set of connected systems, but an ecosystem instead. Brian Eno is fond of ecosystems because they’re closer to how human culture and the earth’s natural systems already behave. “Now this thing about ecosystems”, as he explains, “is that it’s impossible to tell what the important parts are. It’s not a hierarchy, you know. We’re used to thinking of things that are arranged in levels like that, with the important things at the top and the less important things at the bottom. Ecosystems aren’t like that. They’re richly interconnected and they’re co-dependent in many, many ways”.4

On the grand scale humanity has always attempted to create a better future through the continued process of imagining, re-imagining, dreaming, re-dreaming, working and re-working together. Always with the best knowledge we have at our disposal at any point in time. To adapt and ‘re-purpose’ an old Bill Moggridge quote: ‘If there’s a simple, easy design principle that binds everything together, it’s probably about starting with the people and nature, and ending with the people and nature’. To put this in its simplest terms, we’re essentially talking about creating more robust loops for living, aligned closer to earth’s cyclical processes, and then maintaining their harmony.

Illustration – Circles!

Illustration – Circles! Re – Quote #6 — A SIMPLE PRINCIPLE

Re – Quote #6 — A SIMPLE PRINCIPLE

—

Credits & Notes

1

World Energy Council

Resources – Solar 2013

2

Ken Caldeira

Stanford University

via The Guardian – Sun 15 Oct 2017

3

Rahwa Ghirmatzion

PUSH Buffalo

People United for Sustainable Housing

4

International Renewable Energy Agency

REthinking Energy – 2017

World Energy Council

Resources – Solar 2013

2

Ken Caldeira

Stanford University

via The Guardian – Sun 15 Oct 2017

3

Rahwa Ghirmatzion

PUSH Buffalo

People United for Sustainable Housing

4

International Renewable Energy Agency

REthinking Energy – 2017

5

Pilita Clark

The Big Green Bang – How renewable energy became unstoppable

Financial Times – Thu May 18 2017

6

Justin Rowlatt

BBC News – Ethical Man Blog

Wed 11 Mar 2009

7

Powering Texas

poweringtexas.com /

Wind power in Texas

(Wikipedia)

8

Ariel Schwartz

Japan has finally figured out what to do with its abandoned golf courses

Business Insider – 16 Jul 2015

Pilita Clark

The Big Green Bang – How renewable energy became unstoppable

Financial Times – Thu May 18 2017

6

Justin Rowlatt

BBC News – Ethical Man Blog

Wed 11 Mar 2009

7

Powering Texas

poweringtexas.com /

Wind power in Texas

(Wikipedia)

8

Ariel Schwartz

Japan has finally figured out what to do with its abandoned golf courses

Business Insider – 16 Jul 2015

10

Simon Mouat

A New Paradigm for Utilities – The Rise of the Prosumer

Nov – 2016

11

Pilita Clark

The Big Green Bang – How renewable energy became unstoppable

Financial Times – Thu May 18 2017

12

Lauren Gambino

Pittsburgh fires back

The Guardian – Thu 1 Jun 2017

13

Niall McCarthy

Solar Employs More People In U.S. Electricity Generation Than Oil, Coal And Gas Combined

Forbes – Wed Jan 25, 2017

Simon Mouat

A New Paradigm for Utilities – The Rise of the Prosumer

Nov – 2016

11

Pilita Clark

The Big Green Bang – How renewable energy became unstoppable

Financial Times – Thu May 18 2017

12

Lauren Gambino

Pittsburgh fires back

The Guardian – Thu 1 Jun 2017

13

Niall McCarthy

Solar Employs More People In U.S. Electricity Generation Than Oil, Coal And Gas Combined

Forbes – Wed Jan 25, 2017

13

Niall McCarthy

Solar Employs More People In U.S. Electricity Generation Than Oil, Coal And Gas Combined

Forbes – Wed Jan 25, 2017

14

Pilita Clark

The Big Green Bang – How renewable energy became unstoppable

Financial Times – Thu May 18 2017

Niall McCarthy

Solar Employs More People In U.S. Electricity Generation Than Oil, Coal And Gas Combined

Forbes – Wed Jan 25, 2017

14

Pilita Clark

The Big Green Bang – How renewable energy became unstoppable

Financial Times – Thu May 18 2017

Section 1 — Roots

Chapter 1 — An Introduction

Chapter 2 — The Rise and Fall of the Eclectics

Chapter 3 — The Bauhaus Function

Chapter 4 — De Stijl meets Time

Chapter 5 — The Role of the Magazines

Chapter 6 — DADA

Chapter 7 — 3 Letters... War

Chapter 8 — The Ulm Age of Methods

Chapter 9 — Modernism and the Ongoing Project

Chapter 10 — Capitalism Eats Itself

Chapter 11 — Roughly where we stand now

Interlude — Transition

Chapter 1 — An Introduction

Chapter 2 — The Rise and Fall of the Eclectics

Chapter 3 — The Bauhaus Function

Chapter 4 — De Stijl meets Time

Chapter 5 — The Role of the Magazines

Chapter 6 — DADA

Chapter 7 — 3 Letters... War

Chapter 8 — The Ulm Age of Methods

Chapter 9 — Modernism and the Ongoing Project

Chapter 10 — Capitalism Eats Itself

Chapter 11 — Roughly where we stand now

Interlude — Transition

Section 2 — Leaves

Chapter 12 — How do Movements Happen?

Chapter 13 — Energy makes Energy

Chapter 14 — Digital need not be Digital

Chapter 15 — All the Signals of Hope...

Chapter 16 — Defining Sustainabilism

Chapter 17 — Sustainable by Design

Chapter 18 — The Future will take us in Circles

Chapter 19 — Where do we go from here?

Chapter 20 — The Role of the Arts

Chapter 21 — The Value in Meaning

Chapter 22 — Be more Tree

Chapter 23 — An Ending. A Beginning

Chapter 12 — How do Movements Happen?

Chapter 13 — Energy makes Energy

Chapter 14 — Digital need not be Digital

Chapter 15 — All the Signals of Hope...

Chapter 16 — Defining Sustainabilism

Chapter 17 — Sustainable by Design

Chapter 18 — The Future will take us in Circles

Chapter 19 — Where do we go from here?

Chapter 20 — The Role of the Arts

Chapter 21 — The Value in Meaning

Chapter 22 — Be more Tree

Chapter 23 — An Ending. A Beginning